The Knowledge Trap and Other Sacred Cows That Hold Us Back

Generational Transfer of Knowledge

In every era of human history, there has been a place and a need for older generations to pass on what has been learned to generations behind them. The learnings and wisdom of previous generations serve as a platform for progress as a society and prepare young people for successful adulthood. This has taken place formally and informally for all of human history. Knowledge transfer can occur through mentorship, in multigenerational social settings, apprenticeship, and formal schooling. In the modern world, schools play an important role in transferring knowledge from generation to generation.

As we move into the later stages of the 4th Industrial Revolution and the realities of the VUCA world, the nature and needs of generational transfer of knowledge are beginning to shift. With the accelerating pace of change in today's world, the technical knowledge of older generations that dominates school curricula is becoming less and less relevant in preparing students for their future. However, the social, emotional, and developmental needs of young people remain the same over time. The implications of these facts for program and curriculum design are significant. From a content and knowledge perspective, schools need to be nimble and flexible. For example, this year's coding program may have little relevance in two or three years. However, the social-emotional development programming that helps students grow as ethical decision-makers and complex problem solvers will have lasting relevance year over year.

As we look forward to developing future-minded schools we must put developmental needs and skill development at the forefront of our programs. In a rapidly changing world, it is the foundation of what has been called non-cognitive skills that will serve students to be effective, productive, self-assured, and happy adults.

In 2017, Scott Looney, Head of School at the Hawken School wrote - The Future For Education, Why Hawken Has To Lead. In this essential essay, Looney points out that:

"A large body of research in success and happiness consistently shows that "non-cognitve skills" (character traits) like cooperation, resilience, creativity, persistence, empathy, sense of humor, and leadership are far better determiners of lifelong success than academic skills ... the push for greater alignment with a standardized content-driven curriculum left less room for school activities not directly related to the acquisition of content knowledge ... although the best and most creative teachers can find activities that support both cognitive and non-cognitive skills, many schools devote far too little time and energy during the academic day to the development of non-cognitive skills (character traits)"

The Knowledge Trap

In February of 2024, Forbes published an article by John Tamny titled Americans Don’t Gain Knowledge in School, They Create It out of School. In this article, Tamny discusses how the world of innovation is outpacing what happens in schools and that much of what is regarded as essential knowledge in school curricula is outdating itself at an ever-increasing rate. As part of the article, Tamny writes:

"... it’s too easily forgotten that progress is defined by what we don’t know, or don’t need to know, as opposed to what we do know. Traveling back in time to the 19th century, the most crucial knowledge for the vast majority of us then was most likely agricultural. That America’s youth were gradually allowed to forget (or never learn) what used to be so important speaks to progress. Moving into the 20th century, it’s a fair bet that most drivers in 1924 knew how to change their car’s oil, along with its flat tires."

Progress in today's world is happening at a pace that demands schools accelerate curriculum design and development processes. This requires a shift in mindset, a willingness to let go of things, and the understanding that progress means moving on from knowledge that is no longer useful or essential today. What is unique about the time we are living in now, is that "old" knowledge lives in our recent memory.

With stores of knowledge expanding at ever-increasing rates, the content students learn is not as important as how or why they learn. To be clear, content and knowledge acquisition remain important as part of the school experience. Creativity and innovation are dependent on knowing things. The caution here is to be sure that the focus of curriculum and programming does not get unnecessarily limited to content acquisition as the end goal. Rather the focus needs to be an end goal of developing skills and dispositions that will serve the students well into the future. The coding language they learn in high school may be irrelevant in a few years, but the computational thinking skills and associated problem-solving strategies will be useful for years to come.

Of all of the sacred cows that we have in education, the knowledge trap is perhaps the most common and troublesome for transformation-minded leaders. It is because of the notion that content acquisition is king that we cannot let go of a range of traditions and outdated forms (and norms) of teaching. It is also why curriculum balloons and attempts at school transformation come in the form of adding courses, curriculum, or activities without taking away that which has been deemed essential: the acquisition of knowledge across discrete subject areas.

The Sacred Cows

Scott Looney's essay on the future for education does an excellent job of outlining a range of issues related to the knowledge trap. Looney also discusses the nature of the generational transfer of knowledge while advocating for a return to apprenticeship and mentorship as essential aspects of school programming. He also points out the challenges that we face as leaders in the form of sacred cows that educators often encounter as immovable objects in their efforts to make improvements and build relevance in their schools. These sacred cows can be thought of as deeply ingrained (and limiting) mental models that many teachers, parents, and even students have about what school is and what it should be. Looney lists the following sacred cows that you may find familiar:

Separate academic departments

Grade Levels organized by age

Assessment by letter grade and standardized tests

Timed tests

Multiple choice and true/false tests and quizzes

Individual achievement assessment

Teaching (pedagogy)

Whole group teaching

Single content area courses

(lack of) technology-assisted teaching

(lack of) mix of techniques: simulation, projects, internships, discussion, lecture to address the natural range of learning styles in students.

Class size

Use of time (schedule and calendar)

The boundary between academic and co-curricular activities

To deconstruct and remove those sacred cows, transformational leadership grounded in systems thinking is required. Taking on the sacred cows is really about taking on systemic change and focusing on building new mental models about what school can and should be for today's students.

Taking On The Sacred Cows

Sam Chaltain, author of the blog Letters from the Future (of Learning) writes:

" ... reforming a system requires not just the capacity to know your enemy and forge a compelling narrative, but also a systemic approach to the problem - an articulation of the whole. Too often, what happens instead is we lose sight of the whole out of our preference for a specific piece of the puzzle - I call it the sacred cow syndrome. Instead of a unified movement, we get a cacophony of parallel efforts. And instead of paradigm shifts, we get Groundhog Day."

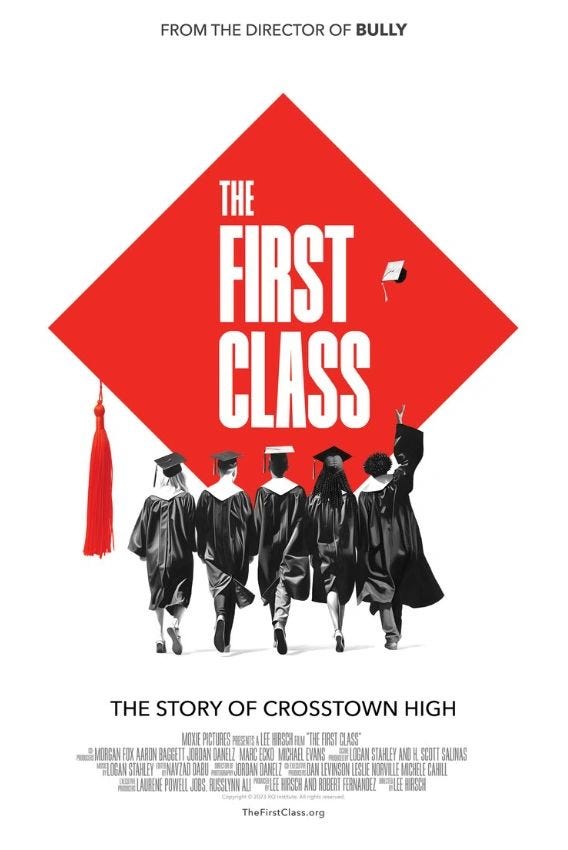

Increasingly, schools are taking on these sacred cows by blurring the lines between work, college, and high school. The challenge in leading such a change is helping others see what good looks like. Fortunately, there are several examples that leaders can look to that will help frame new models for their constituents. The Innovative Models Exchange is a good place to find some inspiration. The XQ Superschools Movement provides another.

Earlier this year, XQ released a documentary called The First Class. What we learn from this film about the founding of Crosstown High School in Memphis, TN is that it is difficult, for a variety of reasons, to take on the sacred cows. Real learning is messy, it is not linear, and students and teachers both have been institutionalized to the degree that taking ownership and producing without a road map induces stress and confusion as necessary shifts are made. In the end, the film shows us that this stress is worthwhile. As school founder, Ginger Spickler points out in an interview for the film:

“ I definitely never saw myself as a school founder. I'm a mom who wants a better school for my kids. A very small percentage of high school kids actually feel engaged in their education. The things that we are asking (of) students have a lot more to do with passing standardized tests and jumping hurdles than they do helping young people make meaning of their lives. They need to see the world in terms of its challenges and what they can bring to it and they need to have the confidence to collaborate with people who are not like them. The world is constantly changing and if we want school to be a place that feels relevant to young people then it has to be responsive to what is happening in the world and what is happening in their lives.”

Conclusion

In an era of acceleration, two things will never change. First, the developmental needs of young people are constant. Second, all high-functioning organizations and communities are founded (and grounded) in core values and shared vision. Focusing on these constants will provide a foundation for growth and innovation as a school takes on the sacred cows. For example, a school is much better positioned to build its identity around the concept of "Every Student, Future Prepared" (a quick shout out to my friends and colleagues at Leman Manhattan Preparatory School), than a school basing its identity around "We had the best AP/IB scores in the county/state/region". In this simple example, the former school is better positioned to change and adapt while maintaining its culture and providing a sense of stability to students, faculty, and families.

The future school is not really about some new high-tech lab, 3d printers, or AI integrations, It's really about leaning into what we know about educational and developmental psychology. When we notice that students are not engaged, and are having wellness issues it's really because their needs are not being met. The innate desire to learn is suppressed in schools for a host of reasons, many related to the scared cows that hold us back. The leadership challenges we face today are about fostering the conditions that allow the innate drive to learn and grow to come to the surface for our students

As Tim Elmore points out in his book Marching Off The Map:

To explain and equip we must relay to our students the timeless ideals that every generation needs to succeed.

To adopt or adapt we must seize what is new and help the students leverage it well.

- Dr. Steven Lyng / gofourthlearn.com

References:

Chaltain, Sam. “How Many Sacred Cows Does It Take to Sustain a Movement?” HuffPost, 28 July 2011, www.huffpost.com/entry/how-many-sacred-cows-does_b_910228. Accessed 5 Apr. 2024.

Elmore, Tim, and Andrew McPeak. Marching off the Map Inspire Students to Navigate a Brand New World. Atlanta, Georgia, Poet Gardener Publishing, 2017.

Looney, D. Scott. “The Future of Education: Why Hawken Has to Lead by Hawken School - Issuu.” Issuu.com, 4 Aug. 2014,issuu.com/hawkenschool/docs/thefutureofeducation#google_vignette. Accessed 7 Mar. 2024.

Tamny, John. “Americans Don’t Gain Knowledge in School, They Create It out of School.” Forbes, 10 Feb. 2024, www.forbes.com/sites/johntamny/2024/02/10/americans-dont-gain-knowledge-in-school-they-create-it-out-of-school/?sh=3e468ed6544a. Accessed 17 Feb. 2024.

“THE FIRST CLASS.” THE FIRST CLASS, www.thefirstclass.org/. Accessed 5 Apr. 2024.